Indian Society and Ways of Living Organization of Social Life in India

India offers astounding variety in virtually every aspect of social life. Diversities of ethnic, linguistic, regional, economic, religious, class, and caste groups crosscut Indian society, which is also permeated with immense urban-rural differences and gender distinctions.

Indian Society Themes

Hierarchy

India has a rigid social structure. Almost all items, individuals, and social groupings are evaluated according to numerous important attributes, whether they are in north India or south India, Hindu or Muslim, urban or rural. Despite having a political democracy, perfect equality is rarely seen in day-to-day living in India.

In almost every sphere of social life, India provides remarkable variety.

Social stratification is visible in caste systems, interpersonal relationships, and family and kinship networks. Castes are typically linked with Hinduism, however Muslims, Indians, Christians, and other religious organisations also have groupings that resemble castes. Everyone in most villages and towns is aware of the relative importance of each caste that is locally represented, and this information continuously influences how people behave.

Additionally, people are graded based on their power and riches. As an illustration, some strong individuals, or "big men," sit smugly on chairs while "little men" approach them to make requests while standing or squatting instead of assuming to sit next to a man of high status as an equal.

Within families and kinship groups, hierarchy also plays a significant role; senior relatives outrank junior ones, and men outrank women of similar age. Family members are treated with formal respect; for instance, in northern India, a daughter-in-law is expected to bow down to her husband, all senior in-laws, and all female household members. Siblings also acknowledge age distinctions, with younger siblings using polite phrases rather than names to address older siblings.

Pollution and Purity

The complicated concepts of ceremonial purity and contamination, which range considerably among different castes, religious groups, and areas, are used to describe many status disparities in Indian society. High status is typically linked to purity, whereas poor status is linked to pollution. Some types of purity are innate; for instance, someone born into a high-ranking Brahmin caste, or priestly caste, has more intrinsic purity than someone born into a low-ranking sweeper caste, or scavenging caste. Other types of purity are more ephemeral; for instance, a Brahmin who has had a bath recently is more ritually pure than a Brahmin who hasn't taken a wash in a day.

Purity is linked to ritual cleanliness, which includes taking daily baths in flowing water, dressing in recently laundered clothes, eating only foods appropriate for one's caste, and avoiding physical contact with those who are significantly lower in rank or with impure things like another adult's bodily wastes. Being involved with the byproducts of violence or death is typically ritually filthy.

Interdependence in Society

Interdependence between people is one of the major ideas that permeates Indian culture. People experience a strong sense of inseparability from the groups they are born into, including their families, clans, subcastes, castes, and religious communities. People have strong bonds with one another, and for many, the thought of being abandoned or lacking in social support is their greatest fear. Family members frequently have a strong psychological dependency. Economic activities are intricately entwined with social interactions. Each individual is connected to kin in nearby and distant villages and towns through a variety of kinship ties. A person can find a relative almost anywhere who can offer moral and practical help.

Social connections can support someone in any endeavour, and their absence might result in failure. Even the simplest activities are rarely completed by one person alone. A young child's mother places the food in his mouth with her own hand while he eats. Someone assists the girl who carries pots of water from the well home in order to dump the pots. A student thinks that a powerful relative or acquaintance can help him get into college. Young people assume that their parents will plan their marriage. Last but not least, a person facing death anticipates that family members will carry out the right funeral rites, facilitating his own peaceful transition to the hereafter and reinforcing social relationships among mourners.

This awareness of connection even permeates theological thought. A kid is taught from birth that his "fate" has been "written" by divine powers and that strong deities who must be maintained an ongoing relationship with him shape his destiny.

kinship and Family values

The fundamental ideas of Indian culture are acquired within the protective embrace of a family. Joint families are highly regarded and should ideally include several generations who live, work, dine, and pray together. These households often consist of unmarried daughters, wives, and male relatives who are related through the male line. Even though she maintains strong links with her birth family, a wife typically lives with her husband's family. The traditional joint household continues to be the dominant social force for the majority of Indians despite the country's fast modernization, both in theory and in reality.

Particularly for the more than two-thirds of Indians who are engaged in agriculture, large families frequently exhibit flexibility and are well suited to modern Indian living. Cooperating kin contribute to the mutual economic security of civilizations where agriculture is the main economic activity. In cities, where kinship links are frequently essential to finding job or financial help, the combined family is especially prevalent. Many well-known families, such the Tatas, Birlas, and Sarabhais, continue to maintain joint family structures while they work together to control significant financial edifices.

The traditional concept of the unified family still has sway, but modern living arrangements vary greatly. Many Indians belong to powerful networks of advantageous kinship ties despite living in nuclear households, which consist of a spouse and their unmarried offspring. Many times, groups of relatives will live next to each other and fulfil their kinship responsibilities with ease.

Joint families generally split up into smaller groups as they grow, which then eventually expand into new joint families, creating a never-ending cycle. To take advantage of job opportunities, some family members may relocate around these days, usually sending money back to the broader family.

Family harmony and leadership

Lines of authority and hierarchy are firmly defined in Indian households, and standards of behaviour aid in preserving family unity. [i] Every family member is raised to respect the authority of those who are placed in positions of authority above them. The family's leader is the eldest male, and his wife is in charge of her daughters-in-law, of whom the youngest has the least power. Those in positions of leadership reciprocally take on the duty of providing for the needs of other family members.

Family unity and loyalty to one's family are strongly valued, especially in contrast to relationships with people who are not related to you. To promote a greater feeling of family harmony within the home, relationships between spouses and between parents and their own children are deemphasized. For instance, it is strongly discouraged for spouses and couples to publicly exhibit their affection.

Males have traditionally held sway over important family assets like land or enterprises, especially in high-status communities. According to traditional Hindu law, women were dependent on their male kin who owned land and structures because they could not inherit real estate. Muslim customary law permits women to inherit real estate, which they frequently do, though typically in smaller amounts than men. All Indian women are now eligible to inherit property under current law. Women have traditionally held some wealth in the form of expensive jewellery for those families who could afford it.

Women's Seclusion and Veiling

Purdah (from the Hindi word parda, which means "curtain"), or the veiling and seclusion of women, is a significant component of Indian family life. Hindu and Muslim women observe intricate restrictions regarding the covering of the body and refraining from making public appearances, especially in front of married relatives and unfamiliar men, in most of northern and central India, particularly in rural areas. Practises related to the purdah are associated with patterns of power and harmony in the family. While there are some significant differences between Muslim and Hindu purdah observances, all kinds of purdah require feminine modesty and etiquette as well as ideas of family honour and dignity. Women from conservative high-status families typically face stricter purdah requirements. [ii] Purdah requires restriction and restraint for women in almost every aspect of life, limiting women's access to authority and the management of important resources in a society controlled by men. Before specific groups of individuals, sequestered women should cover their bodies, including their faces, with modest attire and veils, refrain from adulterous affairs, and only move about in public with a male escort. Women of low rank and income frequently engage in weakened forms of veiling while working in the fields and on construction gangs.

When older male in-laws are present, Hindu women from orthodox families cover their faces and keep quiet, both at home and in public. Even a young daughter-in-law hides her mother-in-law's veil. These customs place a strong emphasis on respectful interactions, restrict unauthorised contact, and strengthen family hierarchies.

Muslims place a strong emphasis on covering up outside of the home, where a traditional woman may don an all-encompassing black burka. Such purdah protects women—and the family's sexual integrity—from unrelated unknown men.

Except for some minority communities, purdah has not been widely practised in south India. Purdah practises are already dwindling in northern and central India, and they are quickly disappearing among urbanites and even the rural aristocracy. Chastity and feminine modesty are still highly regarded, but as options for women to pursue higher education and find jobs grow, veiling has all but vanished in progressive circles.

Life Milestones

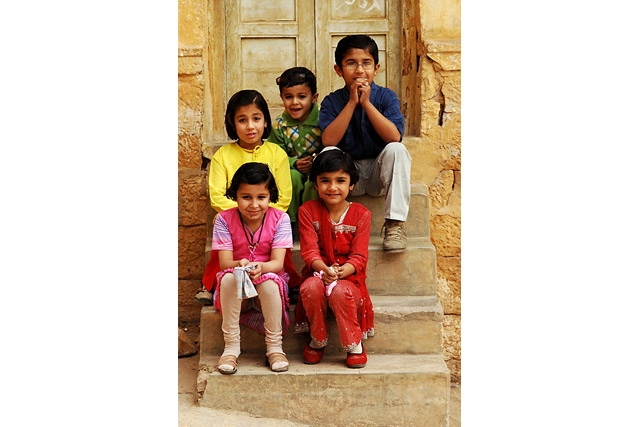

Rituals of welcome and blessing are performed to commemorate the birth of a child, and they are often much more extensive for boys than for girls. Despite the fact that goddesses are widely worshipped in Hindu ceremonies and that India has produced many accomplished women, including the last powerful woman prime leader Indira Gandhi, data show that girls in India face disadvantages. Only 933 females were counted for every 1000 males in the 2001 Census, which was a result of sex-selective abortion, inadequate nutrition and medical care, and occasionally female infanticide. [iii] Parents prefer males since they are more valuable in agricultural work, and after marriage, a boy stays with his parents to help them as they age. A girl, on the other hand, depletes family funds, especially if she brings a sizable dowry to her husband's house. In some communities, dowry expectations have grown extremely extravagant in recent decades.

In India, marriage is seen as a must for almost everyone, signifying the major turning point in a person's life. Marriages between unrelated young people who may never have met are arranged within the caste for the majority of Hindus in northern and central India. Many Muslims and other south Indian communities encourage cousin marriages as a way for families to deepen their bonds with existing relatives. Finding the ideal companion for a child is a difficult undertaking for any parent. People use their current social networks as well as more and more newspaper ads for marriage. Advertisements typically mention religion, caste, educational background, physical characteristics, earning capacity, and occasionally even the size of the dowry (despite though offering or accepting dowries is actually against the law).

Brides and grooms might sometimes meet in academic or professional contexts among the highly educated. Compared to earlier years, 'love weddings' are becoming less sensational. South Asian marriage websites are a common place for brides and grooms to connect among Indians living in North America. Numerous self-arranged unions unite individuals from different castes but with comparable socioeconomic position.

A bride typically resides with her husband at his parents' house, where she must submit to their rule, take care of the home, and bear offspring, especially sons, to further his family's lineage. She should ideally respect her spouse, proudly don her married woman's cosmetics, and happily take on her new responsibilities. If she's lucky, her spouse will respect her, value her contributions to the family, and permit her to maintain contact with her birth family. This is a challenging transition for many young wives. Even while there is still some stigma associated with women working, more and more women are doing so in a range of professions.

Every family is restructured by death. When a woman's husband passes away, she enters the feared state of unlucky widowhood. However, widows of high rank have traditionally been required to stay chaste until death while widows of low status groups have always been permitted to remarry.

Class and Caste, racial, and other distinctions

Although social inequality exists throughout the world, the caste system in India may be the only place where it has been so carefully built. Although caste has been around for many years, it has come under harsh criticism in the modern day and is now experiencing substantial reform.

Castes are ranked, named, intermarriage social groups that are acquired via birth. In India, there are hundreds of millions of people who belong to thousands of castes and subcastes. The social organisation of South Asia is mostly centred on these sizable kinship-based groups. Being a member of a caste gives one a sense of belonging to an established group from which they can expect support in a variety of circumstances.

The Portuguese term casta, which means species, race, or type, is where the word caste originates. Varna, jati, jat, biradri, and samaj are examples of Indian words that are occasionally translated as "caste." Varna, which is sometimes known as colour, actually refers to four significant groups that encompass several castes. The other names are used to describe castes and the caste divisions known as subcastes.

Priests, potters, barbers, carpenters, leatherworkers, butchers, and launderers are just a few of the castes that are connected to traditional jobs. Higher caste individuals typically enjoy greater wealth than lower caste members, who frequently struggle with social disadvantage and poverty. The so-called "Untouchables" were typically assigned dirty jobs. The politically correct term for these groups, which make up about 16% of the population, is Dalit, or "Oppressed." Other groups, typically called tribes (often referred to as "Scheduled Tribes") are also integrated into the caste system to varying degrees. Since 1935, "Untouchables" have been known as "Scheduled Castes," and Mahatma Gandhi called them Harijans, or "Children of God."

In the past, Dalits were excluded from the majority of temples and wells and were to show extraordinary deference to high-status individuals in particular locations. Pre-independence reform movements led by Mahatma Gandhi and a Dalit leader, Bhimrao Ramji (B.R.) Ambedkar, denounced the terrible prejudice that was forbidden by laws enacted during British rule. Dr. Ambedkar almost single-handedly drafted the Indian constitution after it gained independence in 1947, which forbade caste-based discrimination. But Dalits as a whole continue to have serious disadvantages, particularly in rural areas.